Bitcoin (BTC) is a decentralized digital currency system that enables peer to peer value transfer without relying on a central bank or intermediary. It was introduced to the public in late 2008 under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto, who published the paper Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System to a cryptography mailing list. The design built on earlier cryptography and digital cash research, including Hashcash (1997), and combined several core mechanisms into one system: a public ledger (the blockchain), network consensus, and miner incentives.

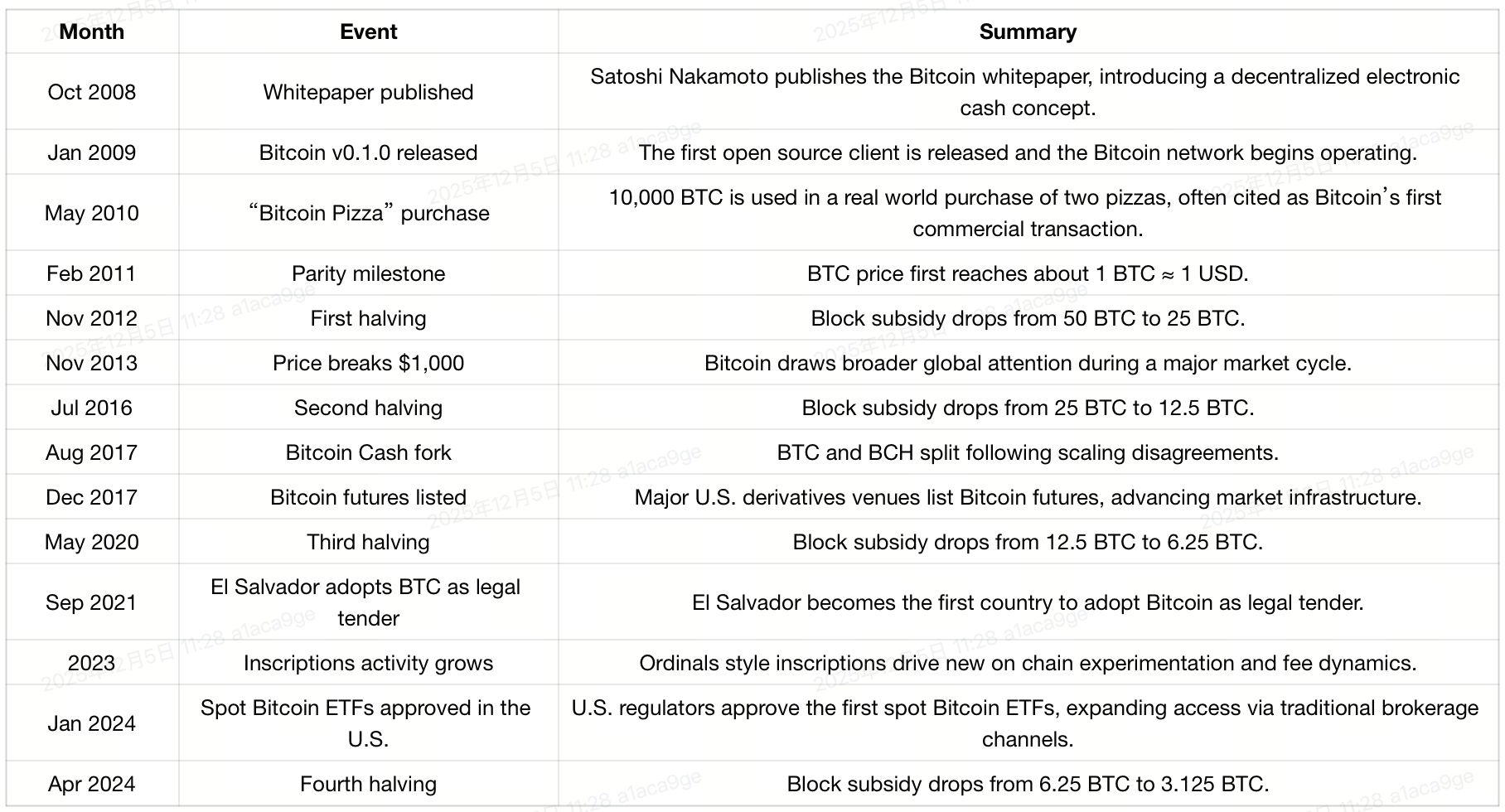

In January 2009, the first open source Bitcoin client (Bitcoin v0.1.0) was released, and the network began operating. One widely cited early milestone happened in May 2010, when developer Laszlo Hanyecz used 10,000 BTC to buy two pizzas. This event is often referenced as Bitcoin’s first real world purchase, and May 22 is now widely commemorated as “Bitcoin Pizza Day.”

1.How Bitcoin Works at the Protocol Level

Bitcoin’s core innovation is a globally shared ledger maintained by independent participants around the world. Instead of a single company or authority controlling the database, the network follows a shared set of rules to decide which transactions are valid and which blocks are accepted.

Blockchain, nodes, and miners

Every new block contains a batch of confirmed transactions. Participants who create these blocks are called miners. Miners compete to propose the next valid block, and the network accepts the block that follows the protocol rules.

Because miners and nodes are distributed globally, there is no single control point. This architecture helps reduce single point of failure risk that centralized systems can face.

Proof of Work (PoW), SHA-256, and mining difficulty

Bitcoin uses Proof of Work (PoW). Miners repeatedly run the SHA-256 hashing algorithm to search for a valid block hash that meets the network’s current difficulty target. Since SHA-256 outputs are effectively unpredictable, miners must attempt many hashes by varying fields such as the nonce until they find a hash below the target. When a miner finds a valid block, it is propagated to the network and can be accepted by nodes.

To keep block production relatively steady at about one block every 10 minutes, Bitcoin automatically adjusts mining difficulty every 2,016 blocks, roughly every two weeks. If the network hash rate increases and blocks are found faster, the difficulty increases. If hash rate drops and blocks slow down, the difficulty decreases. This adjustment mechanism helps stabilize block timing under changing mining conditions.

The halving and Bitcoin’s supply cap

Bitcoin also has a built in issuance schedule. Approximately every four years (every 210,000 blocks), the block subsidy is cut in half. Historically:

- 2012: 50 BTC → 25 BTC

- 2016: 25 BTC → 12.5 BTC

- 2020: 12.5 BTC → 6.25 BTC

- 2024: 6.25 BTC → 3.125 BTC

As halvings continue, the creation of new BTC slows over time. The total supply is capped at 21 million BTC, with the last fractions expected to be mined around the year 2140. This predictable issuance model is one reason Bitcoin is often described as having scarcity properties similar to “digital gold.”

2.How Miners Earn Bitcoin

Mining is the process that both secures the network and introduces new BTC into circulation. It requires real world resources, primarily computing power and electricity. Over the past decade plus, mining hardware has evolved from CPUs to GPUs and then to specialized ASICs (Application-Specific Integrated Circuits). Today, Bitcoin mining is largely industrialized and highly competitive.

Hardware, mining pools, and professionalization

Individual miners typically use ASIC devices such as the Bitmain Antminer series, MicroBT WhatsMiner series, or Canaan AvalonMiner series. After powering hardware, miners usually join a mining pool (for example, F2Pool, AntPool, or ViaBTC). Pools combine hash rate from many participants to reduce payout variance and provide steadier earnings compared to solo mining.

Publicly listed mining companies also contribute meaningful hash rate to the network. Examples often discussed in the market include Marathon Digital, Riot Platforms, and CleanSpark.

Primary issuance versus secondary market purchases

BTC acquired directly through mining is often considered “primary market” issuance, since it originates as newly created coins via the block subsidy. BTC purchased on exchanges is part of the “secondary market,” because it is acquired from other holders.

It is a common misconception that miners always obtain BTC far below market price. In reality, miners face significant costs, including hardware, electricity, facilities, maintenance, and operational overhead. In bearish market periods, Bitcoin’s market price can even fall below the average cost of producing one BTC for some miners.

3.How Investors Can Buy Bitcoin

Most investors acquire Bitcoin in two common ways: through a cryptocurrency exchange, or through peer to peer (P2P) transactions. Each approach has different tradeoffs in convenience, protections, and risk.

Buying through a centralized exchange

Many users prefer regulated or well established centralized exchanges because they provide a structured environment for trading, custody options, and user support. On platforms such as Bitunix, users can typically purchase BTC using fiat on ramps or stablecoins like USDT, and some platforms may support card purchases depending on region and availability.

Before trading, users generally need to complete Know Your Customer (KYC) verification. KYC and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) controls are standard across much of the industry and are designed to meet compliance requirements and help reduce illicit finance risks. In practice, this usually involves identity verification and, in some cases, address confirmation.

Exchanges also commonly use security measures such as hot and cold wallet separation, multisignature controls (multisig), and real time monitoring. As always, users should enable protections like strong passwords and two factor authentication.

Buying through P2P transactions

P2P purchases involve buying directly from another person, often via a marketplace or escrow based workflow. P2P can be flexible and useful in certain regions, but it can also carry higher fraud risk, including impersonation, payment reversal issues, and counterfeit proof of payment scams.

If you use P2P, it is important to follow platform safety guidance, use escrow where available, and thoroughly review counterparty reputation and transaction terms.

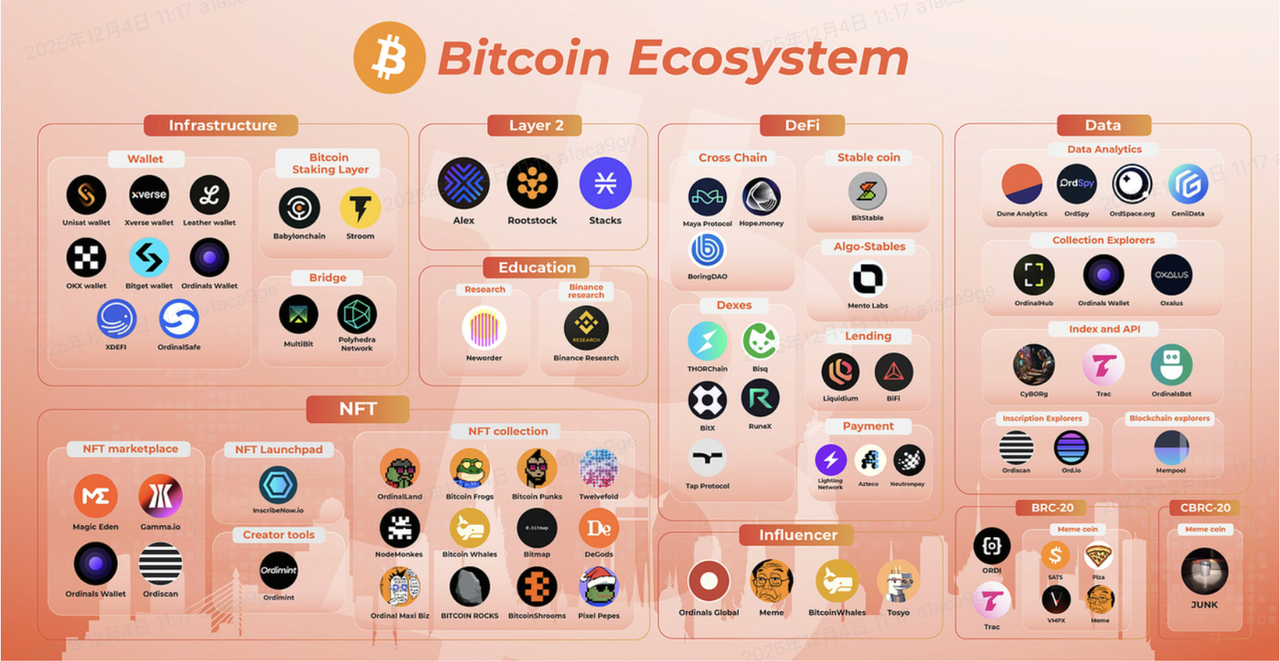

4.The Bitcoin Ecosystem

Since 2009, Bitcoin has grown from a simple peer to peer payment concept into a broader ecosystem that includes scaling technologies, wallets, tokenized representations, and emerging on chain use cases.

Forks

A fork occurs when the network or community splits due to differing views on protocol rules or upgrade paths. A widely known example is Bitcoin Cash (BCH), created in 2017 amid disagreements over block size and scaling approaches.

Layer 2 scaling

Layer 2 refers to systems built on top of Bitcoin that aim to improve speed and reduce costs by moving activity off chain while still settling back to Bitcoin for finality. The Lightning Network is the best known example, enabling fast, low cost payments. Other projects may extend functionality, including broader smart contract or application capabilities, depending on the design.

Wallets

A Bitcoin wallet is how users store and manage private keys and sign transactions. Wallets can be software wallets (hot wallets) or hardware wallets (cold storage). Hardware wallets such as the Ledger Nano X are widely used for higher security storage. Some software wallets are designed for specific use cases, including Bitcoin inscriptions and BRC-20 related activity.

Wrapped Bitcoin (WBTC)

Wrapped Bitcoin typically refers to a tokenized representation of BTC on another blockchain, often backed 1:1 by BTC held with a custodian. WBTC is a well known example used in DeFi contexts on other networks, enabling BTC exposure in lending, liquidity, and trading applications that do not natively support Bitcoin.

Inscriptions (Ordinals) and BRC-20

Bitcoin inscriptions, commonly associated with the Ordinals protocol, allow data such as text or images to be inscribed onto individual satoshis, the smallest unit of BTC. This activity contributed to new experimentation on Bitcoin, including the emergence of the BRC-20 token standard concept. These developments increased on chain activity and sparked new debates about fees, block space usage, and the evolving Bitcoin application layer.

5.Major Bitcoin Milestones (Timeline)

Disclaimer

This article is not intended to provide: (i) investment advice or investment recommendations; (ii) an offer or solicitation to buy, sell, or hold digital assets; or (iii) financial, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Digital assets (including stablecoins and NFTs) involve high risk and may be highly volatile. You should carefully consider whether trading or holding digital assets is suitable for you based on your financial situation. For your specific circumstances, consult your legal, tax, or investment professionals. You are responsible for understanding and complying with all applicable local laws and regulations.

About Bitunix

Bitunix is a global cryptocurrency derivatives exchange trusted by over 3 million users across more than 100 countries. At Bitunix, we are committed to providing a transparent, compliant, and secure trading environment for every user. Our platform features a fast registration process and a user-friendly verification system supported by mandatory KYC to ensure safety and compliance. With global standards of protection through Proof of Reserves (POR) and the Bitunix Care Fund, we prioritize user trust and fund security. The K-Line Ultra chart system delivers a seamless trading experience for both beginners and advanced traders, while leverage of up to 200x and deep liquidity make Bitunix one of the most dynamic platforms in the market.

Bitunix Global Accounts

X | Telegram Announcements | Telegram Global | CoinMarketCap | Instagram | Facebook | LinkedIn | Reddit | Medium